The clouds came rolling in from the west and they were black as coal, moving fast like a locomotive.

Having spent a good portion of his life outdoors as an excavator, Roger Storey, in a field on Stone Road in Pendleton, knew enough to get the heck out of there.

Outside that Friday morning in Niagara Falls, the beagles were barking at the bitter cold and biting wind. Which is not unusual for Western New York. Still, Charles Clark, a snowplow operator getting ready to go to work, had a feeling he should make an exception and put the hounds in the basement with plenty of food and water.

Something was brewing, and it wasn’t the coffee at the Niagara County Jail, where several deputies took a look at the skies and took to their cars, initiating a dangerous journey.

Like thousands of others across Niagara County and Western New York, they would not make it home because the Blizzard of ’77 was getting ready to bury the area.

Escape into the …

Hell froze over and blew into Western New York on Jan. 28, 1977, and didn’t let up for days.

Lake Erie had frozen over earlier than ever that winter, providing a gigantic, perfectly flat repository and launching pad for December’s and January’s record 10 feet of snow.

Although the skies would produce only a few more inches of snow during this blizzard, when the winds gusted well above the highest posted speed limit, the liberated snow from the lake reduced traffic all over the white-washed roads to a blind crawl.

Inside cars everywhere, panic gripped the wheel. “The snow was so bad, I knew where I was only by the mailboxes on the side of the road,” said Sandra Milligan, a Niagara-Wheatfield cafeteria worker trying to make it home to Niagara Falls.

When the mailboxes were on her left, she knew she was in trouble.

All over the county, drivers found themselves fishtailing in zero-visibility, driving into ditches or clear through the middle of farmers’ fields.

Snowdrifts grew by the minute and roads became impassable. Drivers were forced to take circuitous routes home through this dangerous and unprecedented blizzard.

Storey, trying to make his way back to North Tonawanda, turned onto Sunset Drive in the Town of Lockport and saw nothing but a sheet of white.

He slowed his truck to a stop as the wind screamed and shook the vehicle. Then it shook some more. He’d been hit from behind. Jumping outside, he barked at the driver, “Couldn’t you see where you were going?”

“No, not at all,” the driver replied.

“Then why didn’t you stop?!?”

A timely question, as the sound of another sliding car came out of the whiteness. Then it hit.

All over, the roads were in chaos and soon would be deadly. Those looking to survive tried to get indoors, anywhere: businesses, fire halls, the homes of strangers.

In this blinding sea of snow, three Navy officers inched their car westward down Niagara Falls Boulevard.

They passed one stalled or abandoned vehicle after another, some recognizable only by radio antennas peeping through the snow.

Up ahead, a snowdrift as tall as a tree loomed impossibly above the boulevard — too much even for the mammoth plows to break through — sending the black-uniformed trio dashing through the whiteout into Papa Leo’s Pizzeria.

Inside, while disbelief circulated in the crowed room, Petty Officer 1st class Vee Houseman tried to reach her home on a pay phone.

All lines were busy.

Around the county, people scrambled to make sense of their situations as things unfolded.

Royalton-Hartand High School in Middleport was running dangerously low on heating fuel — the trucks didn’t make it that morning for their delivery — and inside, the halls were bursting with 600 students.

In just a few hours, walls of hard-packed ice sealed the school entrances. “So we had snowmobilers coming to the second-floor windows to pick up students,” said Randall Gilbert, a social studies teacher there at the time.

As he scrambled to get as many students home as possible, Gilbert thought about his planned wedding just one week away … and sighed. Instead he’d be settling in with hundreds and hundred of students.

Gimme Shelter …

By 5:30 p.m. that Friday, it was clear to anyone that something epic and monstrous was under way.

Sandy Burdick stood by the flexing window in her parents’ Johnson’s Creek home and held a hand over her belly that had been steadily growing for the past eight months.

She was due any day now, and the 19 -year-old, first-time expectant mother was getting nervous.

Her parents were stuck in Lockport, and she faced the dilemma of staying in this house with her younger brothers or going to a nearby farm owned by Archie Adams.

“At least Archie had delivered a cow before,” she said

In Niagara Falls at WJJL, a “sunset” station allowed to broadcast only until dusk, Tom Darro would normally be calling it a day — a welcoming thing since he’d spent all of the last night reporting on a fatal explosion at a shopping plaza.

Instead, he was calling Washington, D.C., and getting permission to continue emergency radio broadcasts — for five days and six nights, it would turn out.

For many, the broadcasts originating at WJJL and WHLD were vital links to those trapped in cars or isolated in homes by themselves.

At the pizzeria, the sailors decided it was a lost cause trying to make it home, especially after witnessing a cross-country skier traveling alone down the normally busy boulevard.

Instead, they’d make the best of it at the White House bar across the street. “It was especially important they have a TV because none of us wanted to miss the next episode of ‘Roots,'” Houseman said.

Farther south in Cheektowaga, Lockport resident Walter Zebriewski found refuge with his daughter in the toll plaza he worked at. Inside the tiny office no bigger than a two-car garage, he and a dozen stranded motorists — including a very pregnant woman just involved in a car accident — pooled the food and cigarettes they salvaged from their cars.

As the winds outside howled, a single question repeated in their minds: How long can this possibly last?

Hunkering down and making do

Like many businesses across Western New York, the office in Cheektowaga where Olcott resident Cindy Smist worked served as a waystation for 20 out-of-luck motorists from near and far.

“It was kind of festive,” Smist said “We had plenty of food — even beer — and we watched a little bit of ‘Roots.’”

Despite Kunta Kinte’s heart-wrenching journey into and out of slavery, Smist and her co-workers couldn’t help but pay attention to the emergency reports filtering through the media.

“We couldn’t get hold of anybody — parents, sisters or brothers,” she said. They were particularly worried about a co-worker, Dave, who lived nearby, and against their most strenuous warnings, disappeared into the storm.

In Niagara Falls, Milligan made it home, and to keep warm, she spent a lot of time in front of the stove cooking and baking cookies while the family set up camp in the middle of the house on a roll-out bed.

Storey didn’t make it back to North Tonawanda, but instead found shelter at Myron Wasik’s place on Comstock Road along with 41 other stranded motorists — mostly from Harrison Radiator — who played cards all night and drank beer commandeered from an abandoned Shlitz truck.

“Dick Wasik had a wire around his case of beer and the wind blew it right by him,” he said.

The party atmosphere was even more charged at the half-dozen or so hotels in Niagara Falls, where hundreds of the most fortunate found refuge from the blizzard. Lawyers, salesman, railroad workers, reporters and pressmen from the Niagara Gazette mingled into the night, eating, drinking and trading war stories about the blizzard, said veteran Gazette reporter Don Glynn.

“All available women should report to room 151,” Glynn recalls hearing over the intercom at one point during the extended party.

At Roy-Hart High School, the 450 remaining students were being kept as occupied as possible by watching movies and swimming in the heated pool. More importantly, Gilbert said, teachers pulled all the male students aside “and let them know where the tar met the road.” There’d be no taking advantage of the situation, he said.

While there was a very short leash at Roy-Hart, elsewhere, the storm would produce plenty of “blizzard babies” — some conceived and others born — while the storm outside raged on.

The morning after …

After a fitful night of sleep, the Navy folks awoke three abreast and fully clothed in the unheated motel room the manager set them up with for free.

The first thing they noticed was their vaporous morning breath, and then saw the snowy footprints they tracked in last night were identically crisp.

The morning light didn’t reveal any mysteries for plow operator Clark in Niagara Falls. All night through he’d been plowing the “hotspots” — in particular, St. Mary’s Hospital — to make sure they remained accessible in the blizzard, showing no signs of abating.

”You still could’t see where you were plowing,” he said. “It was all guesswork.”

At Wasik’s Curve, Storey was enlisted in the daunting snow-moving effort as well.

“Saturday morning, we got some machines and started pushing the snow around,” he said.

Later, Storey and Bob Swan learned about a cache of snow removal machines — a mile away.

“It was like walking in the mountains,” he said.

When they finally reached the rows of machines, only one would start. The air was far too cold. So they spread a canvas over another bulldozer and lit a blowtorch to heat the air feeding the engine. It turned over.

But the big prize — a brand-new machine 17-feet high and one of the biggest in Western New York — would require 12 hours out in the beyond-bitter elements to assemble the wheels and bucket.

“I had a beard,” Storey said. “That helped.”

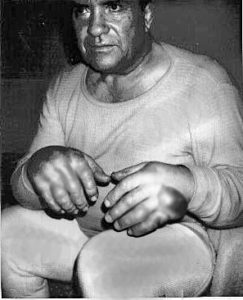

Man suffering from frostbite and exposure.

At the radio stations in the Falls, just as busy — though not as cold — the sleep-starved staff fielded a steady stream of calls.

“If somebody needed something, they called us,” said Eddie Joseph, general manager at WHLD.

In one particular life-threatening situation, Joseph’s wife, JoAnn, arranged the transport of a desperately ill 4-year-old girl to Children’s Hospital via an Air Force helicopter since the roads were simply buried.

Snowmobilers also assisted vitally — like Dorsey Kline and his son, Brad, in Niagara Falls, Bill Hebeler in Pendleton and Paul Camarre, in North Tonawanda, among scores and scores of others — helping to deliver people, food, clothing and medicine through the escalating madness to wherever it needed to be.

As necessary as their work was, though, and as cruel as the wind was that bit their faces and even froze their eyes shut, the snowmobilers were in heaven.

“It was great to be running up and down the streets without the police chasing you,” Camarre said.

Meanwhile, at the toll plaza in Cheektowaga, everyone was doing their best to keep their pregnant companion as comfortable as possible. She was always the first to be served off the temperamental hot plate. Nobody wanted to deliver a baby in those threadbare conditions.

That included 19-year-old Burdick in Johnson’s Creek waiting it out and nervously wondering who was going to hold out longer: her or the storm.

At 1 a.m. Sunday morning, when she felt the first dull twinge of the baby starting its descent, she realized which mother was the bigger force of nature.

The Road Home

With the ambulance siren wailing — overpowering even in the omnipresent wind — Burdick and her sister Nancy held on as the vehicle made its way — rather quickly, they thought — down the slippery, bumpy road to Medina Memorial Hospital.

“Slow down!” yelled Nancy, also expecting. “You’ve got two pregnant woman back here!”

Inside the hospital, while waiting for the doctor to arrive, Burdick for once forgot about the blizzard raging outside.

“All I could think about was how much it was hurting to have this baby,” Burdick said.

Two hours later that Sunday morning, she delivered a screaming baby, Jessica, just as the storm outside began to die down.

When the partiers awoke Sunday at the former Schrafft’s Motor Inn, sunshine and wispy trails of snow danced playfully amidst the arctic formations that had transformed the city streets.

Freed from their air-blasted prisons, stranded motorists now faced the task of getting home, locating buried cars — many whacked or scooped up by snow-moving machines — and digging out.

By Sunday afternoon, Falls plowman Clark finally was relieved after three straight days behind the wheel, and he headed home with one thing on his mind. “I sure hope those dogs are all right,” he thought.

Thankfully, they were. So was his wife who was stranded until Saturday somewhere on Route 104. And unlike some, his house was in one piece — no broken pipes, furnace still going, nothing crushed by the tremendous weight of the snow.

By Monday morning, some semblance of normalcy returned with the familiar sight of postal carriers delivering mail — albeit through shoulder-high tunnels resembling something from an alien ice planet.

“By then, the mailboxes were pretty much shoveled out,” said Middleport mail carrier Russ Gilbert.

It wasn’t until Tuesday afternoon — five days after the storm hit — that the snowed-in county jail guards were bailed out by a new shift, including the guards who had disappeared into the storm and made it only to a farmhouse half-way home.

“It had been like we were the prisoners,” said Deputy Gene Cosgrove, who along with the other guards donned prisoner’s uniforms when they become too dirty.

“We were on one side of the bars, and they were on the other.”

Mother Nature held the key, though.

Roy-Hart’s Gilbert missed his wedding, but he and his fiancee’ Susan were married April 29, 1977, and are still going strong.

And Dave, the guy who ran out into the storm against everyone’s advice was found in his car — alive and taken to a shelter.

Although just a week later, a good portion of the snow melted and green grass could be seen once again, Storey still hadn’t gotten back to North Tonawanda and was still driving around, pushing snow into giant piles — many containing frozen dogs that wouldn’t be discovered until May.

There were at least four blizzard-related deaths in Niagara Country, but far fewer than Erie County’s 30 — found mostly in cars.

Why the blizzard seems to have taken on a life of its own is because it was experienced by so many in so many different ways, according to Enro Rossi, author of “White Death,” a collection of perspectives on The Blizzard of ’77. Some experienced communal deprivation, others’ singular sweat and toil, boredom and isolation or just an opportunity to cut loose with dozens of strangers thrown together by the winds of fate.

It also gave Western New Yorkers a new appreciation for the force of nature, Rossi said.

42 years later, because of it we are more experienced, smarter and better prepared. For the next time …